© Markus Lång 2006

This review was first published in

Lewis Carroll Review, issue 31

(January 2006), pp. 13–16.

PDF version (215 kB).

A Finnish-language version was

published in Valitetut teokset, pp. 413–418.

Jonathan Miller and Childhood

|

Alice in Wonderland (1966) Written by Lewis Carroll Adapted, produced and directed by Jonathan Miller Music specially composed by Ravi Shankar Video format: PAL (4 : 3) Audio: English, Dolby Digital 1.0 Runtime: 71′ 42″ DVD video region code: 2 British Film Institute BFIVD519, £ 19.99 © BBC Worldwide Ltd. 2003 http://www.bfi.org.uk/ |

“It is a film about children, not explicitly for them”, Jonathan Miller commented on his personal adaptation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The film was first broadcasted on BBC at a late hour, 9:05 p.m., on December 28th, 1966. Such timing and attitude caused a scandal and unfriendly comments in the press (“a travesty”).

Almost forty years later this television movie still provides a fresh view on childhood and dreaming. It is not a travesty but a very loyal adaptation of Lewis Carroll’s story; for example, almost all of the dialogue comes from the book, with only a few improvised lines by some actors. The visual language was inspired by Victorian photography and Pre-Raphaelite paintings (and Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez). Miller mentions photographs taken by Carroll and Julia Margaret Cameron as models. All sceneries and sets are such that a nineteenth-century Alice might have seen and known them.

Concerning Carroll’s book, the greatest change is that we see no animals portrayed in this production, only actors and actresses. Miller justifies this in his audio commentary by saying that the animal names could be interpreted as nicknames for persons as well. It is possible to identify all actors who perform in this movie. You see Wilfrid Brambell, not some anonymous actor who wears a gigantic bunny suite, like the corresponding actor in Percy Stow’s (1903) or Nick Willing’s version (1999). The animalism is left to the imagination of the viewer.

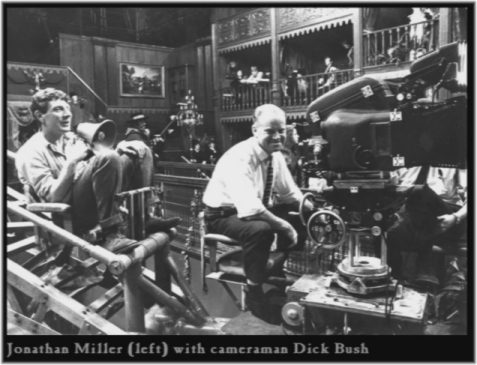

The

visual appearance of this

movie is elegant and sparse. It is black-and-white, the aspect ratio is

1.33 : 1, audio track monophonic, and most of it has been

photographed (by Dick Bush) with a 9-millimetre wide-angle lens, which

gives a deep focus. Some takes remind one of Stanley Kubrick’s

visual style. The deep focus and distortion of the close-ups give the film a

surreal and dream-like appearance.

There was nothing Freudian in

his conception, Miller assures us, although most critics have viewed the

movie in deeply Freudian terms. Miller was not interested in Sigmund

Freud but William Wordsworth and his view of childhood; he disliked

especially the Disney version (1951), calling it “absurd”.

Alice in Wonderland is a very successful dream movie

precisely because it doesn’t aim to be Freudian. Too obvious

Freudianism has ruined many classical movies, like The

Spellbound and Secret Beyond the Door. Despite the

intentions of the filmmakers, Alice in Wonderland can, of

course, be analyzed with psychoanalytical means, and in so doing, one

should be able to point out something new, not simply to

identify the clichés that the filmmakers inserted or avoided.

The essence of dreaming is captured very appositely by Miller. This movie reminds the viewer of the truly great dreamers of the screen: Jean Cocteau (Orphée) and Federico Fellini (Otto e mezzo). The Brechtian alienation (Verfremdung) of the dialogue delivery and abrupt changes of place create a very dream-like and surreal atmosphere, and this seems to be very close to the real essence of dreaming proper. Problems and situations of ordinary life appear disguised in the dream and new solutions are hinted at. Wishful thinking rules in the kingdom of dream: note especially how the bottle with the label “drink me” and the cake with the words “eat me” appear from nowhere and how unostentatiously Alice’s size changes: no amazing trick photography, only a different lens & angle and smaller or bigger furniture. These kinds of changes illustrate the “psychoanalytic understanding of infantile subjective experience as lacking in clear self-representations of any sort and as dominated by inadequate or absent differentiation between what is thought and what is real” (Roy Schafer, Aspects of Internalization, p. 92).

Anne-Marie Mallik plays the central role of Alice. She appears rather expressionless, not dull, in most scenes, talking almost impatiently and harshly to the Wonderland characters, who seem mostly to have only silly things to say — like adults in real life. The viewer must project feelings onto this girl. Her inexpressive performance illustrates the suspension of the reflective self-representations which occur in dreams; when dreaming, one usually is not surprised of the absurd ideas of the dream but takes them for granted. The dialogues do not resemble conversation but recitation; they sound more like rituals, in the vein of Bertolt Brecht. Aki Kaurismäki has utilized the same effect in his movies.

The rest of the cast is more lively and expressive, especially the Hatter (Peter Cook), but his gestures seem nonchalant and out of context — that is, mad. More obvious insanity can be observed in the caucus-race sequence which parodies High Church religion. This scene shows quite mercilessly how a child can experience the outward forms of hypocritical worship: chaotic, empty, jerky gestures totally devoid of substance. I guess Alice feels herself an outsider in her world, and is not sure if she wants to be a member of that fussy adult society.

Miller has interpreted Alice’s story quite extensively as a critique of Victorian society. The Queen of Hearts (Alison Leggatt) resembles Queen Victoria, and the depiction of her court isn’t very flattering. Miller lets a child see the pervasive infantilism of the undemocratic way of life. Alice is like a foreign correspondent observing this ingrained kingdom from the outside (cf. Lettres persanes). On the other hand, the courtroom scene is obviously a childish reconstruction based upon hearsay. The set itself is lavish and surreal (set designer Julia Trevelyan Oman), with a janitor and a gardener, and animal voices in the background. The Queen sews her cross-stitch embroidery during the trial.

The story proceeds without hesitation, but the overall impression is not that of rushing through in a hurry, as in Nick Willing’s version, for instance. Miller mentions that the first rough cut was 20 minutes longer, and Huw Weldon made him shorten it considerably — with favourable results.

For a small-scale production, the cast is most impressive. Anne-Marie Mallik is a perfect choice for an alienated Alice. Her calm expression carries the film from the first take to the last. The White Rabbit is played by Wilfrid Brambell, whom many may nowadays remember as Paul’s clean grandfather from A Hard Day’s Night. Sir Michael Redgrave as the Caterpillar and John Bird as the Frog Footman so aptly portray adults who have nothing meaningful to say to a child. Leo McKern’s Ugly Duchess is surely one of the most memorable and exuberant drag performances ever seen on film before and after Dame Edna. The Mad Tea-Party, which is hosted by Peter Cook (Hatter), Michael Gough (March Hare) and Wilfrid Lawson (Dormouse), surely creates the impression of exhaustive timelessness, when riddles and other pastimes turn into their dire opposites: you are supposed to be amused by a riddle without an answer, and a story without the least sense in it (“They lived at the bottom of a well”). Sir John Gielgud (Mock Turtle) and Malcolm Muggeridge (Gryphon) personify old men who still (or finally) glorify their ancient school days and dance by the sea; their childhood has nothing in common with that of Alice. Peter Sellers brings quite a lot of dotage to his role of the King of Hearts, including slapstick that Miller slightly disapproves in his commentary.

One of the most alienating (and refreshing) factors in this production is the music. Miller approached Ravi Shankar and asked him to provide music for the film. So we mostly hear the unusual combination of sitar and oboe in a British production of a very British classic. Miller mentions that the sound of the sitar is meant to invoke the buzzing of insects in the summer nature. Because of the Beatles, the sound of the sitar reminds one irresistibly of the sixties, but the music is still alive and exciting. I could not imagine a happier film score for a production like this.

Miller’s Alice in Wonderland has been seen rarely, and a new release is most welcome. The British Film Institute has produced a beautiful digital transfer of the movie and put it on DVD. The original negative appears to be in rather good condition; some fading can be noted, but otherwise no film deterioration is apparent. Also video artifacts are very few indeed; the clarity and sharpness of the image is preserved. The audio track is monophonic and the sound is clear and free from hiss and distortion. One needs a region-2 or region-free DVD player and a PAL-compatible equipment to view this disk, but a similar release for region 1 exists.

The disk provides some extra

features as well: full-length audio commentary by the director, and the

first Alice movie ever made, Alice in Wonderland

by Percy Stow from 1903. Although in a bad condition, this silent movie

runs 8 ½ minutes, and has an audio commentary by

Simon Brown. Add to this Miller’s biography, production

photographs and an essay by Philip Kemp.

Carroll is not the only author that Miller used in this production. At the end, Alice quotes from Wordsworth’s ode “Intimations of Immortality”:

“It is not now as it hath been of yore; —

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.”

Due to the efforts of film archivists we can still see Miller’s vision clearly facie ad faciem, from face to face.